A simple explanation that hopefully doesn’t overload our limited working memory.

As teachers we know how easy it is to confuse people. Our brains are the most incredible objects in the universe, capable of amazing things. Yet somehow I still manage to get confused when someone starts trying to show me a new spreadsheet and I crumble without my Teams calendar.

So why is it that we get confused? Why do our students struggle to comprehend concepts that seem easy? My journey to understanding this and fully empathising with my students came from cognitive load theory. I began to understand the cognitive psychology which governs how our brains process information.

Dylan Willam famously tweeted in 2017 about the importance of CLT (see below).

Given how transformative CLT has been to my understanding of my students’ cognitive processes, I’m inclined to agree with Willam. And it’s also really interesting – I really geek out over this niche little interest of mine. In this short article, I’ll try to explain this model of human thinking.

Human Cognition

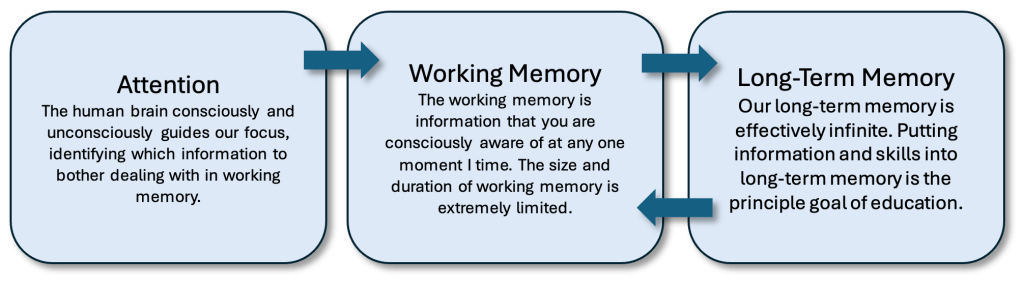

Our current best model of how humans think involves three fundamental components; attention, working memory and long-term memory.

Attention is incredibly important, and there is a lot to be said about how we improve our student’s attention (literature on the attention contagion is a good start). However, for now, cognitive load theory mainly deals with the interaction between working memory and long-term memory. Our objective as educators is to change long-term memory so that the information and skills students learn is accessible to them later (next week or next decade).

Working memory is very limited, being able to store or process between 4-7 elements of information at any one moment in time. Yet working memory is essential because all information must be processed in working memory to eventually be encoded into long-term memory. This means that the working memory is a bottleneck to learning; the flow of information into long-term memory must be slowed down as it passes through working memory.

This bottleneck is actually an evolutionary advantage because our brains need a safeguard in place to avoid always rewriting all of our hard-earned knowledge. If we assimilated all information from the environment without rigorous processing, then our long-term memories would be a very confusing mass of random ideas. Crucially all learning must be actively processed in working memory, as opposed to passive attempts at absorbing information.

With this basic model in mind, we can see that supporting the processing in working memory is essential for learners to cope with the flow of information during learning. I will briefly discuss some of the implications of this for teaching and learning below.

Experts vs Novices

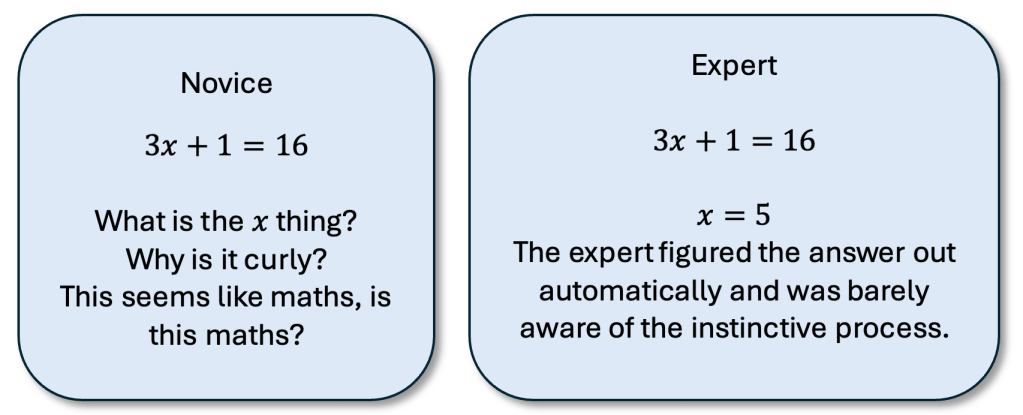

Cognitive psychologists have identified a clear distinction in the thinking between domain novices and domain experts. For example, I am a novice in the domain of orthoperiodic surgery (trust me, I know zilch), and if someone tried to talk to me about it, I would get very confused, tired and bored very quickly. However, an expert in the field is able to process huge amounts of information from this field with ease and conduct complex surgery in stressful conditions.

This means that the cognitive processing of information that we’re familiar with is different to processing information that is new. New information is effortful and slow to process as it must be processed entirely in working memory. Familiar information is supported by relevant schemas in the long-term memory which activate automatic (often subconscious) processing enabling rapid and effective thinking.

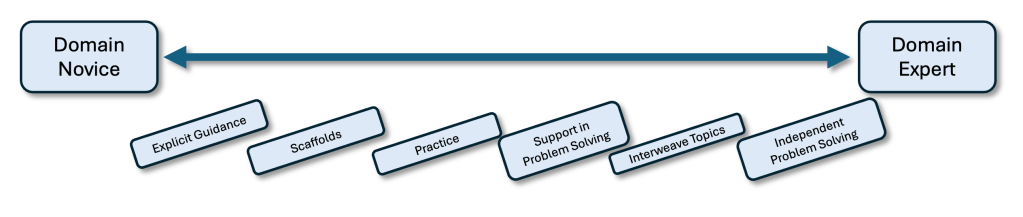

This eventually leads to a phenomenon in cognitive load theory called the expertise reversal effect. As learners develop fluency, knowledge and confidence in a domain (examples: French grammar or writing complex sentences), they are able to continue challenging themselves and work independently with less guidance. Until then, they are closer to the novice end of the spectrum and need strong scaffolds, explicit guidance and corrective feedback.

Cognitive Load Effects

To illustrate the power of CLT, I will explain two cognitive load effects. These effects are predicted and explained by CLT, and they have been demonstrated and replicated in randomised control trials (scientific experiments) worldwide in a variety of settings – a reminded that cognitive psychology is a thorough scientific field meriting the consideration of our profession.

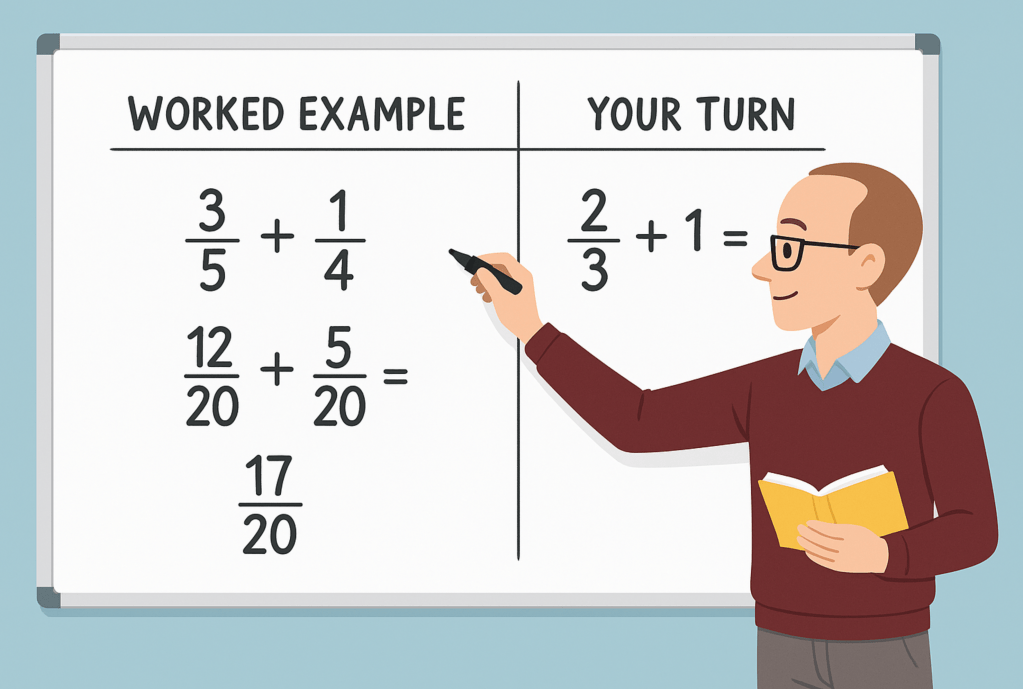

The Worked Example Effect

Worked examples are fully guided models of how to answer a question. There is experimental evidence that students gain more understanding, meaning and knowledge from worked examples than less structured approaches or less guidance. This is in line with the predictions from the model of human cognition explained above; worked examples are capable of breaking problems down into chunks which are easier to process in the limited working memory.

The Transient Information Effect

Transient information is information which disappears before it has been fully encoded into long-term memory. Definitions on a PowerPoint slide may vanish after a transition, whiteboards with worked examples maybe erased too quickly or and spoken instructions can fade from listeners’ minds within seconds. As a result, students must actively recall newly introduced ideas to effectively engage with the activity. This transient information imposes an unnecessary burden on the working memory, as students are exerting cognitive effort on the irrelevant task of recalling the novel information. That cognitive effort would probably be better directed towards actively applying the ideas and engaging in sense-making activities.

To avoid this, I often split my whiteboard into two halves. On the left I explain a complete worked example, annotate it with guidance and leave it visible. Then on the right, I write a similar problem for students to attempt on their mini-whiteboards. By leaving my example as a prompt for the novice students, I avoid imposing an unnecessary cognitive hurdle on the students when they need to develop their confidence.

| Other cognitive load effects. I’d recommend you reading more about common cognitive load effects. They are subtle obstacles to cognitive processing which you may not have recognised before. | |

| Split Attention Effect | When students have to constantly redirect their attention between two sources of information for them to understand something, this imposes an unnecessary cognitive load. For example, a diagram with a separate key, or a worked example split onto two sides of a sheet of paper is surprisingly difficult to understand. |

| Redundancy Effect | Excess redundant information complicates things, rather than adding support. |

| Self-explanation Effect | Prompting students to generate their own explanations of concepts is an effective way of supporting and encouraging active cognitive processing. |

Little Jimmy in Class

Jimmy is new to the school in Year 5. At his previous school he learned in his native language, yet he is confident in English. Today he is learning about adding fractions with different denominators.

In his previous school they used slightly different notation and methods, so although he has some prior knowledge, it is difficult to keep up with the pace of the class who are all more practiced and familiar with the current approach. His long-term memories are not able to fully support his working memory processing.

Jimmy tries to follow along, and while he understands each word and phrase, he has to actively translate it into his mother tongue in order to fully understand. This added layer of cognitive processing is taxing on his working memory.

The teacher shows a worked example, but Jimmy misses an opportunity to ask about a particular step before the example is erased. He can remember step 1 and does so diligently on his mini-whiteboard but struggles with step 2 and beyond. The steps and scaffolds were too transient. This knocks his confidence in maths.

Jimmy also doesn’t know his 6 times table. So, when a particular problem requires this knowledge, he has to work it out through repeated addition. He tries hard, but this burden on working memory overwrites his vague recent memories of which question he was on and why 4 x 6 = 24 was relevant in the first place.

Unfortunately, Jimmy becomes cognitively exhausted. His brain is getting tired from the excessive cognitive processing required to access this task and he begins to lose interest in today’s lesson. A feeling I’ve experienced many times before. Jimmy learns little, loses his self-esteem and doesn’t get to experience the gratification of learning that he deserves.

With a better understanding of the hidden cognitive mechanisms which underpin how students learn, we can begin to adapt our teaching to try to avoid these pitfalls. Cognitive load theory is a very important lens to view teaching and learning through.

Summary

I could have written a book, and indeed much clever writers than I have indeed written awesome books on cognitive load theory. I would definitely recommend Cognitive Load Theory in Action by Oliver Lovell for more depth into the theory and practical suggestions. Rosenshine’s Principles of Instruction are also an excellent guideline to follow for practical classroom strategies based on cognitive psychology. I find cognitive psychology fascinating, and having a theoretical insight into the hidden lives of learners helps me become a better teacher every day.

I have skipped over some key ideas in this article. I didn’t mention the three types of cognitive load (intrinsic, extraneous and germane). I didn’t mention the difference between biologically primary and biologically secondary knowledge. And I didn’t go into much detail on the nuances of the CLT model either. For this, I’d recommend reading some of the academic literature from the field. My favourite papers can be found here: https://addvancemaths.com/clt/

As with all educational recommendations, I also encourage you to critically evaluate the evidence base of my claims. Andrew Watson’s book, The Goldilocks Map is a brilliant introduction to dealing with the world of educational research.

If you are using cognitive load theory to inform your practice, I’d love to hear how. Please comment below!

Will Mcloughlin

Maths Teacher

Creator of www.addvancemaths.com

Doctorate in Education Student